Why Peer Learning Fails to Take Root

Over three decades of observing organisational learning in action, five recurring barriers stand out:

- No formal design.

“Learning circles” launched without purpose quickly lose energy. Without clear outcomes, facilitation, or follow-through, good intentions dissolve into busy calendars. - Lack of psychological safety.

Learning demands vulnerability. If employees fear judgment or competition, they share cautiously or not at all. Safety, not skill, is the foundation. - Absence of rhythm.

Peer learning needs cadence – defined sessions, reflection cycles, leadership visibility. Without rhythm, it becomes an interruption rather than a habit. - Invisible impact.

Because peer learning lacks obvious metrics, its value often goes unseen. When budgets tighten, what can’t be measured rarely survives. - Cultural disconnect.

In hierarchical or siloed organisations, teaching peers may feel presumptuous. Without recognition systems that value contribution, knowledge remains locked within roles.

When these barriers persist, what begins as community quickly becomes fatigue.

The Architecture of Peer Learning

True peer learning operates simultaneously on three levels:

• The structural level – the systems, platforms, and processes that connect peers meaningfully.

• The behavioural level – the trust, facilitation, and feedback that make those connections productive.

• The cultural level – the norms that celebrate contribution over competition.

Each level requires deliberate design. Which is why peer learning cannot be treated as a grassroots movement alone; it must be a leadership priority and an organisational capability.

At Chrysalis, we’ve seen that when peer learning is designed with precision – when it has architecture, ownership, and rhythm – it moves from initiative to infrastructure.

From Informal Exchange to Institutional Capability

Getting peer learning right doesn’t mean turning it into another formal program. It means balancing the authenticity of community with the discipline of design.

Three principles make that balance possible.

- Design with Intention

Every effective peer-learning system begins with clarity of purpose.

What capability are we trying to strengthen? What knowledge needs to travel across levels or locations? What behaviour should become visible on the ground?

When outcomes are clear, design follows naturally – cohorts with shared stakes, communities of practice with defined goals, feedback mechanisms that capture real improvement.

One large technology organisation discovered that its delivery managers needed to move from execution to consultative selling. Instead of a conventional classroom intervention, we helped them form Peer Skill Pods – cross-site groups that analysed client cases and exchanged live proposals. Within months, confidence rose, conversations deepened, and conversion improved.

Intent, not instruction, drives momentum. - Enable the Right Actors

Even the most elegant design fails without the right enablers. Peer learning depends on three roles:

• Leaders, who sponsor the effort and normalise learning from one another.

• Facilitators, who create the environment for exchange without dominating it.

• Learners, who own their growth and make their learning visible.

Each needs preparation. Leaders need stories that demonstrate vulnerability. Facilitators need the tools to guide, not lecture. Learners need reflective prompts, templates, and nudges that keep dialogue alive.

Technology strengthens this ecosystem. Digital platforms such as GLYDE – the Chrysalis Learning Experience Platform – make peer learning visible and measurable. They allow communities to share artefacts, document insights, and recognise contributors. Analytics transform what was once invisible into data that sustains attention and funding.

But technology alone doesn’t create engagement; it amplifies what culture already allows. - Embed It into Culture

Peer learning endures only when it becomes part of how work gets done, not an extra effort outside it.

Embedding requires culture work:

• Agreements that define learning as everyone’s responsibility.

• Systems that integrate peer learning into talent and performance processes.

• Recognition that celebrates mentors and catalysts.

• Role models who learn publicly and teach openly.

• Architecture – the time, space, and tools for exchange.

At one FMCG client, establishing Peer Learning Champion Networks – employees recognised for enabling knowledge flow – increased voluntary learning participation by over 40% within six months.

Culture gives design its heartbeat.

When Peer Learning Works Best – and When It Doesn’t

Peer learning thrives in contexts where knowledge is abundant but under-shared, where collaboration fuels innovation, and where the half-life of skills is short.

It is most effective when:

• Organisations are navigating transformation or digital adoption.

• Teams are cross-functional and interdependent.

• Leadership wants reflection and dialogue to complement expertise.

• Succession and mentoring are critical.

It is less effective when:

• Internal expertise is scarce and must be imported.

• Hierarchy limits openness.

• Learning lacks recognition or time.

Peer learning cannot replace formal instruction. But it can dramatically accelerate its impact by translating concepts into conversation and practice.

The Advantages – and the Discipline Behind Them

When designed well, peer learning delivers multi-dimensional value.

• Relevance: peers teach what’s current, not what’s archived.

• Engagement: learning becomes participative and personal.

• Scalability: insights spread faster than any course catalogue.

• Retention: teaching reinforces mastery – the “learn by teaching” effect.

• Culture: it builds connection, inclusion, and trust.

But these benefits come with a condition: discipline.

Without design, facilitation, and measurement, enthusiasm alone cannot sustain momentum.

Peer learning is the easiest concept to start – and the hardest to keep alive.

What the Best Organisations Do Differently

Across industries, the most successful adopters of peer learning share three traits.

- They treat it as a capability, not an activity.

It’s built into leadership development, onboarding, and project reviews – not run as a side initiative. - They invest in facilitation capability.

Every peer network has trained catalysts who know how to hold space for learning. - They measure both contribution and change.

They recognise those who share knowledge and track how peer learning translates into collaboration, innovation, or retention.

In these environments, peer learning becomes self-perpetuating – a quiet but powerful current of shared intelligence.

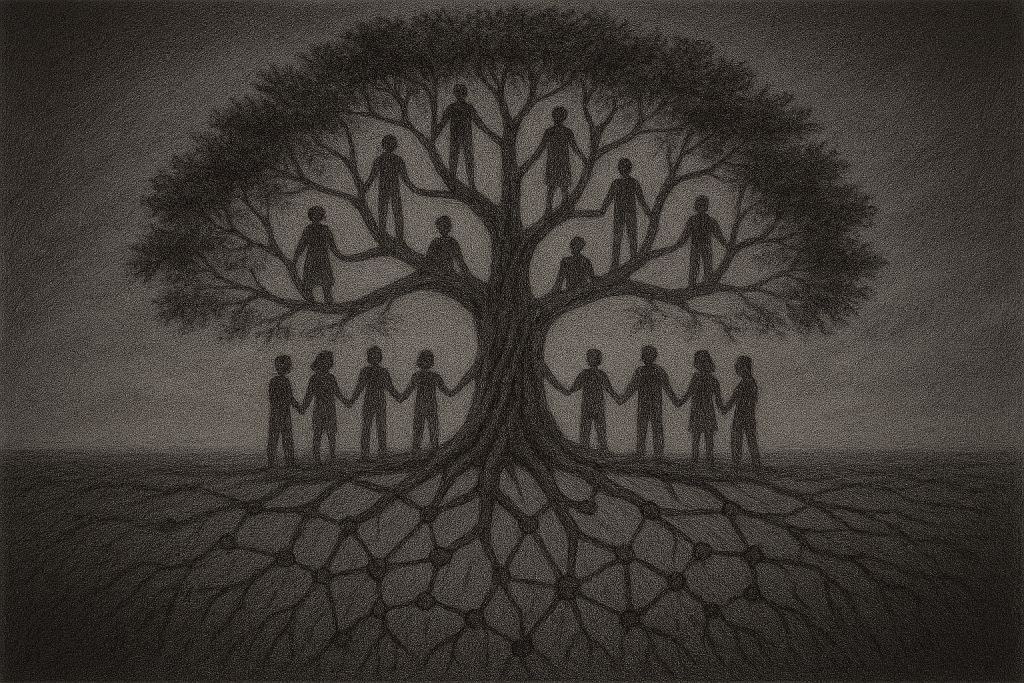

Why This Matters Now

The modern workplace is flatter, faster, and more interdependent than ever before. No single function can own knowledge, and no leader can keep pace alone.

As automation reshapes work and the half-life of skills shortens, the only sustainable learning advantage is collective intelligence – the ability of an organisation to renew itself through its people.

Peer learning is not a trend. It’s the operating system of that renewal.

It asks something both simple and radical of leaders:

to trust that capability does not flow top-down, but across.

When organisations learn to design for that, they build resilience that no tool or technology can replicate.

The Future of Learning Is Collective

At Chrysalis, we’ve seen this truth play out in every transformation journey – across industries, scales, and geographies. When people learn together, they move together.

The future of capability building lies not in creating more experts, but in enabling more exchanges. Not in teaching faster, but in connecting deeper.

Because sustainable learning cultures are never built by a few experts teaching many. They are built by many peers teaching each other – conversation by conversation, project by project, capability by capability. That is how organisations truly learn.