Walk into any organisation today and you will find leaders talking earnestly about capability building, about preparing their workforce for an uncertain future, and about transforming culture so that people become more adaptive, collaborative, innovative, and resilient. Yet beneath this language of ambition lies a quieter, more uncomfortable truth that many leaders sense but rarely articulate openly: organisations do not fail because they lack information; they fail because they cannot get people to behave differently even when they know better.

The great challenge of our time is not one of knowledge scarcity but one of behavioural inertia. And inertia, as every psychologist will tell you, is rarely overcome through more content, more frameworks, more slides, or more cleverly packaged learning journeys. It is overcome only when people truly understand why they behave the way they do, what prevents them from changing, and how their minds, emotions, habits, and environments either reinforce the past or create the conditions for the future.

For decades, corporate learning has placed its faith in the idea that if you teach people enough, something inside them will shift and the change will begin. But the human mind does not operate like an empty vessel waiting to be filled; it operates like a layered, intricate system driven by habit loops, emotional triggers, cognitive biases, social contagion, and an overwhelming desire for predictability. Unless learning journeys engage these psychological levers, they remain intellectually appealing yet behaviourally inactive – impressive on paper but ineffective in practice.

The Knowing–Doing Gap: A Psychological Problem, Not a Learning Problem

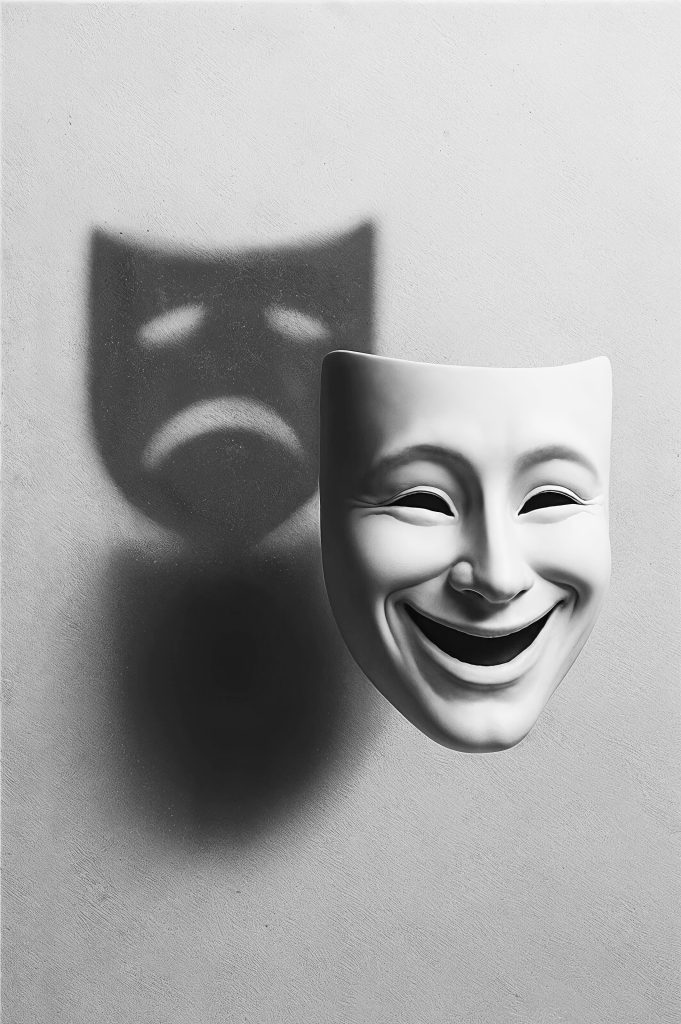

Most organisations today suffer not from a lack of knowledge but from what researchers have long described as the “knowing–doing gap.” People are fully aware of what good leadership looks like, what collaboration should feel like, what customer centricity requires, and how innovation must be encouraged; yet when the moment arrives to behave in alignment with that knowledge, their actions often retreat into the familiar grooves of habit.

This happens not because employees are unwilling or incapable, but because nearly half of human behaviour is habitual – encoded so deeply that it bypasses conscious intention altogether. Research from Duke University reminds us that almost 45 percent of our daily actions unfold on autopilot; we repeat what is emotionally safe, cognitively efficient, and socially reinforced.

This is precisely why capability building cannot rely on content alone. Content may awaken awareness, but awareness rarely changes behaviour unless it is accompanied by repeated practice, emotional insight, structured reinforcement, and environmental cues that make the new behaviour easier to perform than the old one. Leaders who return from workshops often carry with them a renewed sense of clarity, yet the gravitational pull of their everyday environment – the meetings, the pressures, the cultural norms – quickly drags them back into familiar routines. The brain is simply doing what it is wired to do: conserve energy by choosing the path of least resistance.

What Behavioural Science Reveals About How People Actually Change

Over the last two decades, behavioural science has offered profound insights into the mechanics of human change, insights that leadership development has been far too slow to integrate. Daniel Kahneman’s work on cognitive bias, BJ Fogg’s behaviour model, James Clear’s writing on habit formation, Charles Duhigg’s articulation of the habit loop, and the extensive research on psychological safety by Amy Edmondson all offer a common conclusion: behaviour changes only when systems, emotions, and environments change alongside knowledge.

Fogg’s model is deceptively simple yet enormously consequential for capability building. He states that behaviour happens when motivation, ability, and a trigger converge. Most organisations over-invest in motivation, hoping that inspiration will compensate for lack of ability or poorly designed triggers. Yet in reality, people do not persist with behaviours that feel effortful, ambiguous, or unsupported. They persist with behaviours that are easy to begin, rewarding to repeat, and reinforced by their environment.

This is where the field of learning often stumbles. It assumes that motivation and exposure are enough, when in fact the science is unequivocal: without behavioural design – the thoughtful shaping of cues, rituals, feedback, social reinforcement, and emotional anchoring – learning remains theoretical. Change becomes aspirational rather than habitual.

Why Traditional Learning Models Struggle to Create Sustained Change

The traditional “event-led” model of learning creates a burst of cognitive energy, but it rarely engages the psychological forces that sustain transformation. This is why McKinsey’s research repeatedly shows that only a small fraction of capability-building efforts create real business impact: people understand the content, but the behaviour does not shift because the system around them does not shift.

Most learning journeys collapse for four psychological reasons. First, they demand behavioural change without redesigning the environment that cues behaviour in the first place. Second, they stimulate awareness but offer little opportunity for deliberate practice – the kind Ericsson identified as the bedrock of mastery. Third, they overlook the role of emotional meaning, forgetting that people change far more readily when the behaviour connects to their identity, not just to organisational priorities. And finally, they do not build reinforcement loops, leaving new behaviours unsupported and therefore unsustained.

In other words, we design learning for understanding rather than for habit formation. And it is habit formation, not content comprehension, that determines whether organisations grow or stagnate.

Reimagining Capability Through the Lens of Behavioural Design

If capability building is to produce real transformation, then our approach must move away from information transfer and toward behavioural architecture. This does not mean abandoning content; it means recognising that content is only the first layer in a multi-layered psychological process.

A behaviourally intelligent approach to capability does three things simultaneously. It makes the desired behaviour easier to perform than the behaviour it seeks to replace. It embeds the behaviour into existing rhythms so that change does not feel like an additional burden but like a natural extension of current routines. And it makes progress visible, socially reinforced, and emotionally meaningful so that people feel invested in the change rather than instructed to comply with it.

Such an approach transforms learning into a living system rather than a scheduled event. It brings psychology into the heartbeat of capability building, recognising that change must be nudged, scaffolded, reinforced, and emotionally anchored if it is to endure.

The Collective Psychology of Organisations

Behaviour change is rarely an individual phenomenon inside organisations. It is collective, contagious, and heavily shaped by the behaviours that leaders model. Psychologists refer to this as “social contagion” – the idea that behaviours spread not through instruction but through observation.

When leaders reflect openly, seek feedback visibly, practise new behaviours consistently, and admit fallibility without fear, they become psychological triggers for their teams. Their behaviour signals what the culture values, what the organisation rewards, and what people can safely emulate. Without this modelling effect, capability efforts remain fragile, because people will always align with what leaders do, not what they say.

This is why true capability building must integrate behavioural science not only into the learning journey but into the leadership ecosystem. The culture must be designed to reward curiosity, reinforce practice, normalise vulnerability, and celebrate behaviour movement rather than mere knowledge consumption. Only then does change become shared, sustained, and scalable.

Towards a More Human Strategy for Capability

If organisations want people to think differently, they must design differently. If they want people to behave differently, they must shape the conditions in which behaviour lives. Capability does not grow in the classroom; it grows in the small, everyday decisions that people make under pressure, under ambiguity, and under scrutiny.

The future of capability building therefore demands a profound shift in mindset: from content-heavy interventions to psychologically intelligent systems; from teaching to triggering; from learning events to behavioural ecosystems; from cognitive understanding to emotional and behavioural integration.

In the end, transformation will not come from knowing more. It will come from behaving differently. And behaviour will change not because we build better programs, but because we build a deeper understanding of the human beings behind the behaviour.

Because organisations do not change when information increases. They change when people do – slowly, steadily, and with a psychological foundation strong enough to make new behaviours feel not just possible, but inevitable.